Many materials by the Isotype Institute can be found in online digital repositories. The Medialab website provides links to the most interesting and diverse publications.

The first decades of the C20th brought the theory of a universal knowledge system by Paul Otlet, the idea of the World Mind by Herbert G. Wells, as well as the Isotype universal visual language – the subject of Medialab’s particular interest.

The Isotype visual language positions itself at the intersection of the development of computational techniques and modern media. While the former helped society cope with information overload, and the second created an alternative model of perception, Isotype combined the two trends to offer a promise of a universal tool for describing reality.

Isotype’s most important legacy is the transformation mechanism of converting figures into images using a specially developed visual language. The person responsible for such transformations acts as a gatekeeper, and sometimes a curator, whose task is not so much to find a neutral way from the data to the image, but mainly to endow the facts with meaning.

“It is the responsibility of the 'transformer' to understand the data, to get all necessary information from the expert, to decide what is worth transmitting to the public, how to make it understandable, how to link it with general knowledge or with information already given in other charts. In this sense, the transformer is the trustee of the public”. (Neurath 2009, 77–78)

Transformation is a design process which involves defining the relationship between data and image. It is an attempt to use figurative language to present abstract relationships and concepts. It is often based on the search for synthesis and even breaking the Western culture’s traditional opposition between image and natural language, between quantitative and qualitative values, between the tangible and the abstract as well as what is individual and what is collective.

Among the ample legacy of Isotype books, we find the Modern Man in the Making (Neurath 1939) of special interest. A proposal to describe the history of mankind in a publication whose size and format are more akin to a geographical atlas, than an academic monograph, reveals a typical modernist ambition – if not conceit – that synthesising vast historical knowledge is a feasible task.

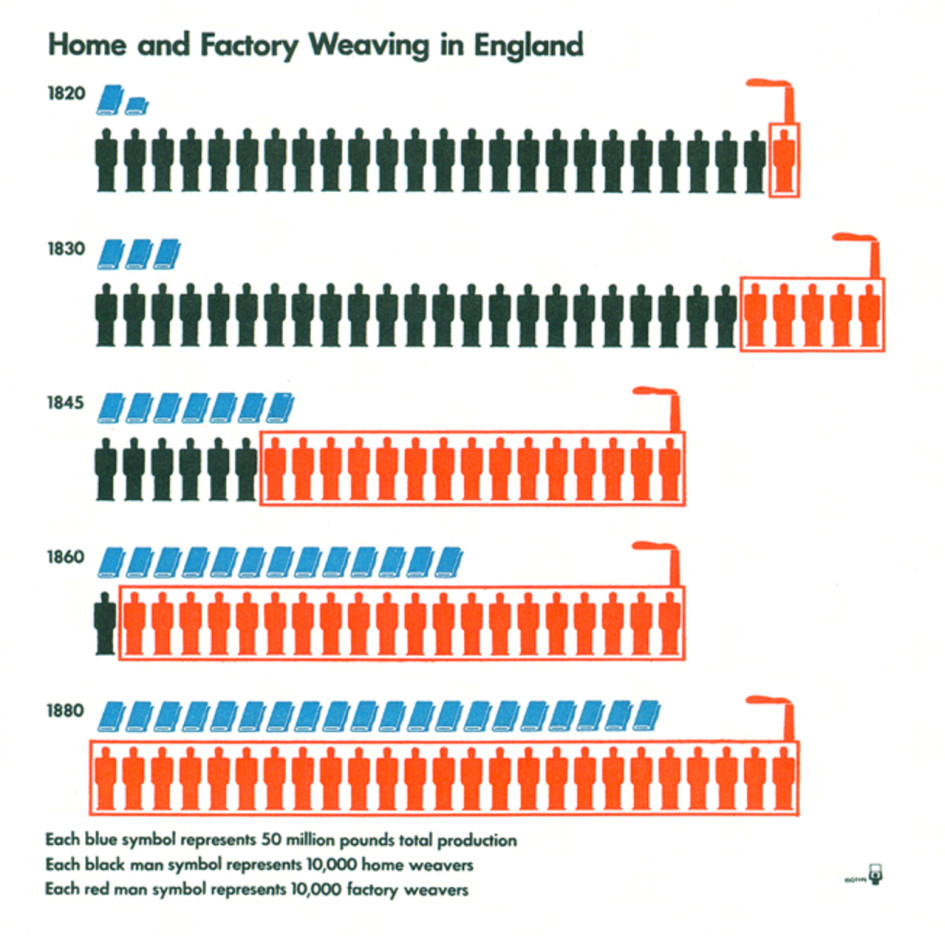

Importantly, the authors are not interested in traditional historical narrative focusing on political events or wars. Instead, they give their utmost attention to social and economic issues and their impact on human emancipation. Even the type of content presented, e.g. statistical data on economic output, demographics and quality of life, forces the use of a data-driven approach to storytelling. In one of the visualisations, designed by Gerd Arntz, authors try to capture the essence of the industrial revolution by showing the way textile production changed between 1820 and 1880.

Arranged in neat rows, the pictograms present both the volumes of fabrics produced and the numbers of workers employed respectively in family workshops and industrial plants. The subsequent years show an increase in productivity, as production shifts to large factories. After 70 years, the same number of weavers is able to produce over 20-fold more cloth. Other visualisations in this publication use data on working times, fertility rates, or average incomes to show how people’s living standards changed in the most industrialised countries.

Isotype work available online

- Visual History of Mankind (book series)

- Modern Man In The Making

- Gerd Arntz Archive: a collection of the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

- Social security: the Story of British Social Progress and the Beveridge Plan

- The Volta river project: what it means to you

- De Moderne Mensch Ontstaat: een reportage van vreugde en vrees

- Internation Picture Language